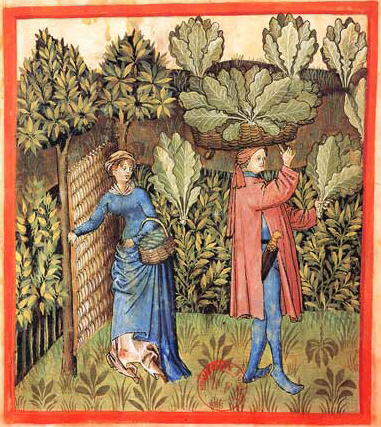

A medieval vegetable garden was an important source of nutrition for our ancestors of the past. Let’s dive into what it would have looked like…

Ever wonder what folks in the Middle Ages grew in their gardens? More than we realise, we owe much of our gardening knowledge and traditions nowadays to the culture of the mediaeval period. You can say that much of culture in that period was centered around horticulture.

The Benedictine Way

The civilization of the Medieval Era as we know it today, was forged mostly by the influence of the Western monastic orders. The first of these orders was the Benedictine Order, founded by St Benedict (480-547 AD). At that time, the world was a wild array of petty kingdoms, tribal communities and remnants of old Roman provinces. The monks of St Benedict established communities of stability under the motto of Ora et Labora: “Pray and Work”. Here the goal was a balance of religious, academic and agricultural activities. Indeed, it is said that the Benedictines civilized Europe “by crozier, by book and by plough”. Our family of the Rohdehof Homestead has been inspired by the Benedictine way over the years so much that we have taken Ora et Labora to be a motto for ourselves as well.

Much of the “science” of gardening was developed within the peaceful walls of the monastery. We have much to thank from these monks and nuns. Many works concerning plants have survived from that period: such as those of Walafrid Strabo, an abbot of Reichenau Abbey, and St Hildegard von Bingen.

An Brief Intro to Understanding Medieval Diet

Society, since the late Stone Age, has been built on the cultivation of grain–wheat, barley, rye, and oats. Prosperity was largely dependent on good weather for a good harvest. Periods of hunger and famine were a hard reality. That is why it was sensible and necessary to have a diverse source of food. In other words, if the grain harvest was poor, one would hope that the vegetable garden could supplement the diet.

Not only that, but vegetable gardens were not taxed. And unlike grain, processing vegetables did not require milling at the local mill–for which one had to pay a fee.

Medieval diet differed between the classes. The aristocratic classes had the gut that handled “finer” foods liked finely sifted wheat better whilst the farmer folk consumed “rougher” fare like rye.

The medieval perception of the human gut and digestion was that it was like simmering pot. The different foodstuffs had to be eaten in a certain order. This is the origin of having the different meal courses. Not following that order could result in poor digestion with uncomfortable (and smelly) consequences. Starting a meal with a sugary drink like Ypocras or mulled wine was meant to open up the “pot”(i.e. stomach) , followed by light greens and soup. Gradually you worked your way up to the heavier foods (considered to be beef and pork). Cheese was the final course to “top off” the pot.

For the daily fare, the ever important bread was accompanied by pottage–a stew with ingredients that varied according to the time of year.

Common Medieval Vegetables

Here are some of the staple crops that would have gone in the pottage. This is by no means an exhaustive list; but it is enough to give a good idea. Something to bear in mind: Much like today, gardens and culinary tastes varied greatly according to culture and region. It is tempting for us to lump the “Mediaeval era” into a big homogenous entity without taking into account the the great colorful variety and differences that spanned Europe ranging from the Mediterranean all the way to Greenland.

- Parsnip

- Pea: Sweet pea varieties came about later in history. In the Middle Ages, peas were more like the “field pea” variety and were thus grown on a larger scale–treated more like grain. They were a staple for both man and beast–being an important source of protein. From this crop, folk made pease pudding and horse bread.

- Carrot: though not the orange variety we are familiar with today. They were more commonly white

- Fava bean

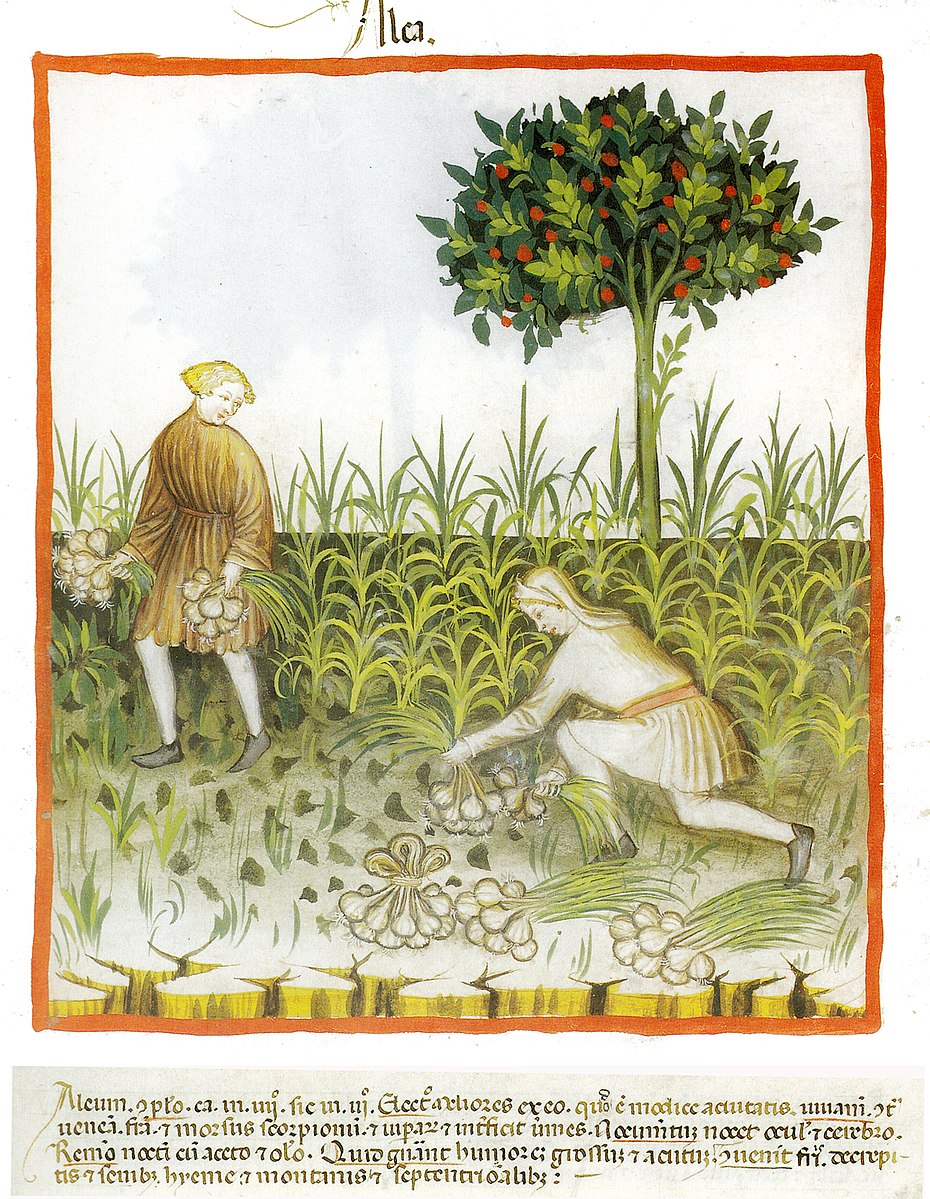

- Leek: An emblem of the Welsh people, being ascribed to their patron St David in the 6th century.

- Onion

- Shallot

- Garlic

- Cabbage: an important non-grain staple crop. It could be easily preserved for Winter by fermenting it into Sauerkraut.

- Kale: Like most brassicas, this was an important cold-hardy crop that could last on the stalk long into the Winter in the milder parts (such as Britain)

- Turnip

NOT Found in a Medieval Vegetable Garden

In order to give us context for where our vegetables came from, these following crops originated in the New World; and thus not known in the Europe before 1492:

- Tomato

- Maize (American corn)

- peppers

- Cocoa bean

- Squash

- Pumpkin

- Potatoes! Why, however did we survive before we had potatoes? “Quite happily and easily,” my children would say…

Edible Weeds

Many of the weeds that irritate irksome suburbanite of today were staple food of our ancestors. Here are just some common weeds that have still have good potential of providing nutrition as much back then as now:

- Purslane: rich in Omega 3 fatty acid. That’s another fancy term that means “something that is good for you”)

- Clivers. Also a good food for poultry! Read more about that here.

- Garden Rocket or Arugula

- Goosefoot, or Lamb’s quarter: A relative of quinoa. Both leaves and seeds are edible. I find the leaves can be used much like spinach. There is archaeological evidence from Northern Germany and Scandinavia of its seeds being prepared for food as far back as the Neolithic Age (4000 BC)

- Plantain

- Nettles! Read more about our adventures with nettles

Cooking Herbs

The herb garden is another vast subject. There was a vast study and use of herbs for medical as well as culinary purposes. But here are a few that were commonly used for the cooking pot

- Parsley

- Dill

- Sage

- Rosemary

- Fennel

- Mint

- Basil

- Chives

- Chicory

- Tarragon

- Angelica (popular especially in Nordic lands)

Why Not Grow a Medieval Vegetable Garden?

Hand’s on History is the best way to engage children in the past. Why not grow a medieval vegetable garden as an educational project? Naturally, it leads into using the produce to make some period-authentic dishes– another great way to build interest in the past…

Historical cooking and recipes coming soon!

~ Nathanael

On a related subject, read about the essential homestead gardener’s tool

Leave a Reply